▶️ Press Play: An Interview with poet Emily Mohn-Slate

"My pause has made me more deeply grateful for any time I have to write."

Welcome to The Long Pause, a newsletter about being creative, being stuck, and what to do about it. I’m Erinn. I’m a writer and an artist in a long, long Pause.

Today’s post is part of the Press Play interview series, which asks creative folks to share the story of their Long Pauses so we can all feel a little less alone in our creative lives. Read on for poet Emily Mohn-Slate’s story about writing from fragments, tough choices when it comes to balancing work, family, health, AND creative practice, and the mindfulness that grounds her. Lots to learn here—enjoy! 💖

Explain yourself. Who are you, how do you identify as an artist / creative?

I’m a poet and essayist and I write the Substack newsletter, Be Where You Are, about how to use writing and mindfulness to live more fully where you are. I’m working now on my second poetry collection and my first book of creative nonfiction. I also teach virtually for the Madwomen in the Attic writing workshops at Carlow University.

I’m a Pittsburgh native, but I recently relocated to Los Angeles, and I’m still adjusting. Moving is far more awkward and messy than I remembered. It throws all the things into the air and forces you to figure out how to hold them differently. I’m spending a lot more time parenting because I’m working part-time and my kids are not in aftercare at their new school—all these forces have altered the shape of my creative life in ways I’m just beginning to understand. I feel like I’m slowly coming back to some core version of myself as a writer, the version that’s rooted in noticing the textures of the world around me in a deeper way than I could access when I was living inside the massive moving to-do list.

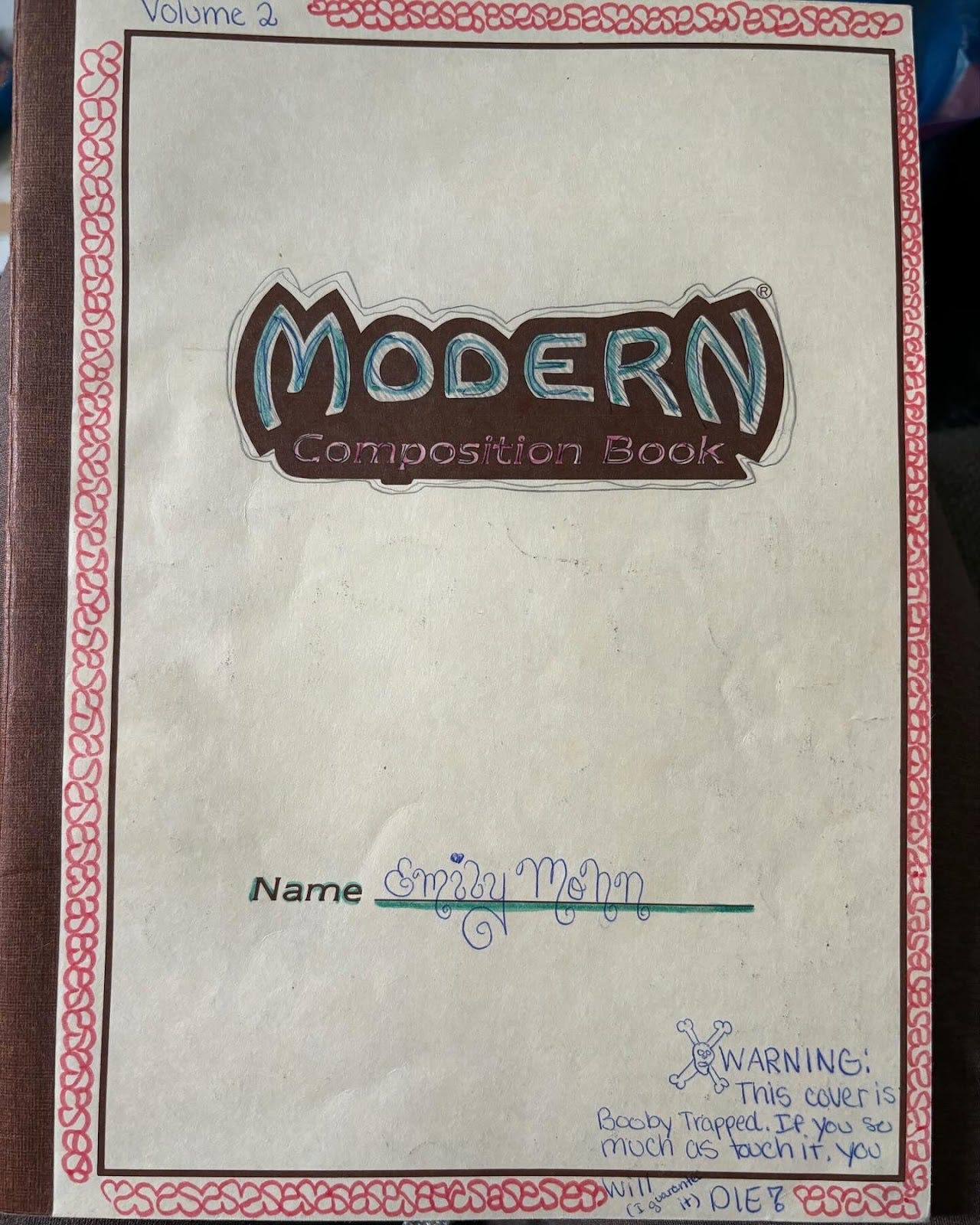

This observant part of me feels like the bedrock of my writer self, one I can track to the Emily pictured above. The Emily whose elementary school librarian passed her a copy of Harriet the Spy—& who started writing down all the little things she noticed that nobody else seemed to notice or care about. When I read Mary Oliver for the first time in college, I lit up with the line, “To pay attention: this is our endless and proper work.” She named the job description I’d already quietly given myself so many years earlier.

You’re here because you’ve gone through a fallow period where you didn’t produce much work for an extended period of time. How did your Long Pause come about? How long did it last? OR are you still in it?

My long pause began in 2020 when I started teaching high school English full-time in addition to teaching for the Madwomen in the Attic. It was Deep Pandemic Times. I had three new classes to prep, I was advising a group of 9th graders, and learning how to teach a Madwomen workshop for the first time. It was an exciting time because I was embedded in two rich learning communities, where I felt inspired intellectually and creatively by my colleagues and students. I had a visceral sense of purpose. I felt I was finally using all the different skills I’d been honing for many years. But I was working constantly—I mean constantly—waking up early to prep and staying up late to grade because my days were taken up with teaching and caring for my own kids through their virtual school days.

My long pause in my writing life was the time I felt most powerful in my teaching practice— but I was using nearly all my creative energies to develop and enrich others’ writing. I didn’t regret it at the time, and I still don’t—I felt so high on that sense of purpose, to be honest, except for the odd moment when another writer would ask what I was working on and I’d stumble to answer. Anyone who teaches knows that teaching itself is a wildly creative practice and often a deeply satisfying one (also sometimes soul-crushing, too). But for me, I just couldn’t keep my writing going and teach in the way I wanted to—and, then if you are also taking care of anyone else in your home—whew! [Nancy Reddy’s Good Creatures interview series features many writers talking about this very quandary]. Every year, when I’d get to summer, it would take me weeks to recover enough to figure out what I even had to say, and then I’d need to start prepping my courses for the next year.

During my pause, I was still kind of writing, but only in fragmented ways to prompts that I gave my students. [I wrote this piece about this process and “how short bursts of writing build to something more”; I wrote this piece about what I did with these short bursts of writing]. I now have two big piles of half-finished, unrevised drafts of poetry and prose living on my desk. For me, it takes mental space and longer stretches of time to be able to revise and actually finish a draft. I have to be able to see the piece fully to be able to know what it needs, to hold the various iterations in my head. And, when I’m rushing from email to email or someone is asking for snacks or help with homework, I can’t do that deep work. Maybe some people can, but I can’t.

I left my high school teaching job this past June because my husband started a two-year sabbatical and we decided to move our family to Los Angeles for that time. It was very painful to leave this position and beloved school community (something I’ll write about in more depth eventually) but it had to be done. It was the right decision for my health (I have chronic migraines), my family, and my writing. My kids are 8 and 10 right now and I have this visceral feeling of how fast they’re growing (my son is technically a “tween?!”) I knew that by scaling down my teaching work, I could be more present for them, and that felt more important to me than toughing it out. I also wanted to devote more time to my writing. I want to make real progress on the two book projects that have been calling to me from these piles of drafts for years now.

How did your Long Pause change your creative practice? Has anything shifted in terms of process or medium? What does your work look like on the other side?

My pause has made me more deeply grateful for any time I have to write. When I can close my email tab and sit with a draft and put words to experience. When I have the time to look up a better word for something in a draft that I know isn’t landing quite right.

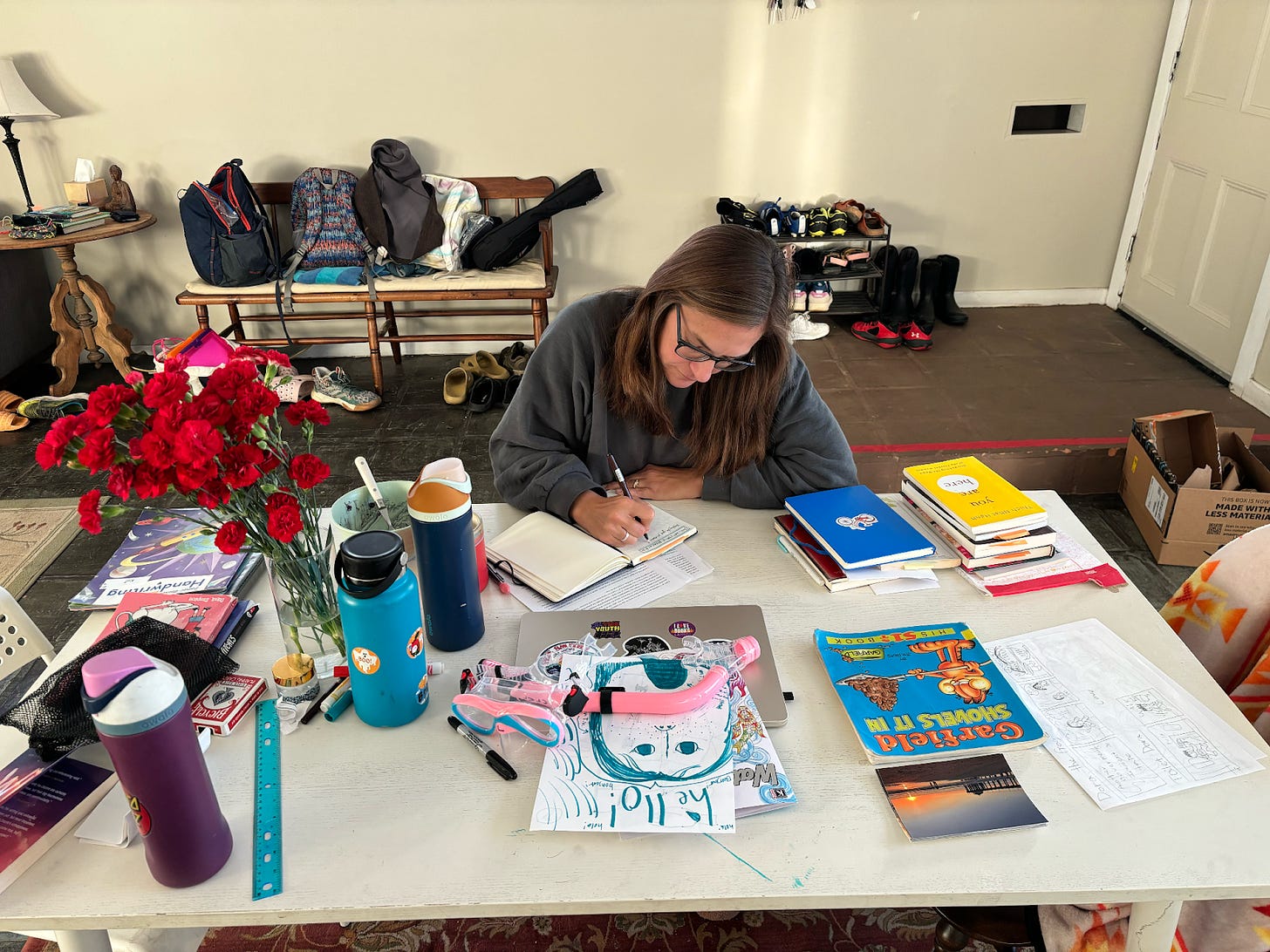

For now, my creative practice looks like writing at the kitchen table in the mornings by hand, then working on whatever essay or poem draft is at the top of my pile for as long as I can before I have to prep for a workshop or pick up my kids. For now, it looks like not finishing a single draft of anything that I can submit yet, but just doggedly pushing the needle forward.

I feel like I’m building a creative practice from scratch with tools I used to be able to wield in my sleep that now I struggle to hold.

For now, my process looks like fragments I type into my phone at a red light, like a voice note I ramble into my phone in the snack aisle at Target. It looks like the shape of my current notebook (decorated in stickers by my daughter), with reading notes, questions, teaching ideas, a few good lines here and there, all moving forward chronologically in time, not to any particular destination, but just a reflection of a life engaged in observing the world and the questions that are mine to explore.

Were there positives that came out of your Long Pause? What did you learn or come to terms with while you were blocked?

What came out of my long pause was a different way of thinking about what it means for me to be a writer. I was able to finally dismantle the idea that I had to be publishing writing to be a writer. I’d been telling my students for years, “If you write, then you’re a writer, and you can claim that title.” But I didn’t believe that advice applied to me.

Early on, I realized one way to survive was to see my intense teaching schedule as creative in itself, and that any lines I produced were just icing on the cake. All of this was freeing. It meant I didn’t need to be losing sleep, or obsessively in the know about the literary and publishing world to be a “real” writer. It helped me re-shape my expectations into something that resisted the larger narrative about constant productivity and publication as the ideal. I could actually be proud that I’d written at all, even if it was a few lines in my notebook that I might not come back to until summer. They were mine—I had fought for them—and they would wait for me.

I could find joy again in the process over the product, which is so trite that any writers reading this are probably rolling their eyes, but really—have you tried actually enjoying the writing itself and letting that be enough? Because that is truly a mindfulness process that is hard as HELL, but feels so deeply good in the end. And here I want to point to something you said, Erinn, in your interview at Be Where You Are: “My life doesn’t have room for what my creative practice used to look like without compromising stuff that’s also important to me, but the alternatives just make me mad. Writing in fits and starts with a resigned “keep on trucking” attitude makes me mad. Giving in and saying “I can’t work like this; I am hitting pause until I can” also makes me mad.” This resonates deeply for me, and helps me feel less alone in not being able to romanticize the struggle into a pithy “but now I see the interruptions themselves as beautiful!” because that doesn’t ring true.

My pause has helped me to live out my friend, poet Jennifer Stewart Miller’s advice that “There is a time for writing and there is a time for living and filling the well. It’s ok sometimes to just fill the well.” When I had my first child, I was just finishing up my MFA at Bennington, and I was terrified I’d never write again, never finish my first book. Jen said to me, “Even if you don’t have time to write a draft, jot down notes, details, moments, phrases. Otherwise, you’ll lose them. You can always come back and write a draft later.” Her own three kids were already teens and young adults and she had lived out a path of doggedly writing down details and fragments and she knew. Even though my kids are older now and I can sneak in longer sessions while they’re doing things on their own, I still hang onto this advice in busy times, or when we’re traveling as a family and there isn’t any time for me to write beyond my morning journaling time when they’re still asleep.

I guess I’m learning how to be a full human being again, with writing as a part of my life and as one of my passions, not eclipsing every other part of me and dictating how worthy I feel.

I’ve learned that I can do the writing and even, sometimes, the thinking in odd moments, and carry the thread of working out a problem while I’m waiting for my daughter’s waffle to toast or waiting at the dentist’s office—but I can’t think in more complex, extended ways, and that's what revision takes. That’s what it takes to finish a draft.

I read that Marianne Moore used to walk around her apartment with whatever poem she was currently working on stuck to a clipboard. While she was vacuuming or doing other practical stuff she had to do, she would still be looking at the poem, she would have it nearby. I love this image and although I don’t use the clipboard method, I try to always have my current draft in my head, so I can turn it over and over until I can bring it closer to what it’s supposed to be.

Has anyone provided a model for you in terms of the ebbs and flows of a creative life?

It means a lot to me when writers talk frankly about their own pauses (one of the reasons I love the interviews in this very newsletter!) I cling to these like a life raft of evidence that you can come out of a long pause and keep going.

An incomplete, unwieldy list of evidence:

—Jean Valentine’s long pause

—what Nancy Krygowski said here, “It’s taken me a long time to be comfortable admitting this, but I’m a very erratic writer. I take long periods of time off from writing without any guilt.”

—what Jan Beatty has said many times to me: “Just keep going. Never give up.” Embedded in that advice are the inevitable pauses. Of course there will be pauses. How could there not?!? We are not machines (thank god). But then you just keep going.

—what Lucille Clifton said: “I don’t write out of what I know; I write out of what I wonder. I think most artists create art in order to explore, not to give the answers. Poetry and art are not about answers to me; they are about questions.” If I can focus on wonder and questions, right away I feel like pauses are ok. They are natural and maybe even good.

—Thich Nhat Hahn and Tara Brach’s writing and teaching have helped me immensely. Their mindfulness, Engaged Buddhist, and self-compassion practices have given me a path to walk that feels new and like it applies directly to my creative life.

I’m always reading Thich Nhat Hanh these days. Two lines I draw on a lot are, “Is my perception accurate?” and, “Nothing exists as a permanent entity; everything changes.” Both help me shift my internal reality so that it’s a bit more porous, more able to see and hold nuances.

Tara Brach said in a meditation once, “What would your life be like if you didn’t believe the limiting thoughts? Who would you be then?” I have this written in my journal because just asking myself that question is incredibly freeing.

Through my meditation and other mindfulness practices, I’m learning a new way to hold my creative work more lightly, with compassion, while also being really clear about why I won’t give up trying.

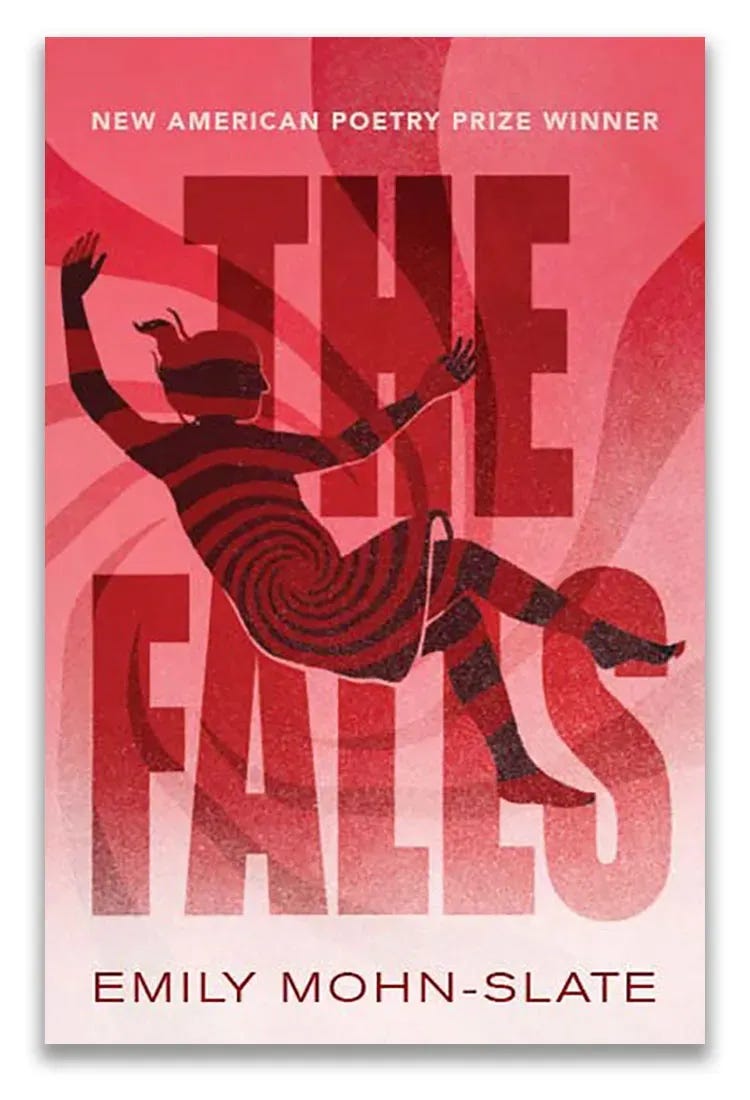

Emily Mohn-Slate is the author of The Falls (New American Press) and Feed (Seven Kitchens Press) as well as other essays and poems. She’s a Pittsburgh native, but she now lives in Los Angeles, where she works as a writer and writing teacher. She currently teaches writing workshops virtually for the Madwomen in the Attic at Carlow University.

You can find Emily on Instagram, Facebook, and Blue Sky, or find out more at her website.

You can find her Substack newsletter, Be Where You Are, here.

Great interview. Also I love seeing a picture of a kitchen table with actual stuff on it, being used as a part of life instead of as a (completely unattainable!) perfectly bare surface!

Thank you for this!