Press Play ▶️ An Interview with Christine Hyung-Oak Lee

"Being demoralized and ripped down to the studs can lay bare the essence of what you desire."

As a gardener and an aspiring farmer 👩🏻🌾 I LOVED reading Christine’s story about how profit/loss sucked the life out of joyful gardening for her— and how that translated to her writing post-Pause as well. I love a good anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchy argument, and this one is a gem. Enjoy— and don’t miss Christine’s Substack, Cuddle Fish, which I’ve really enjoyed! 💖

Explain yourself. Who are you, how do you identify as an artist / creative?

I’m a writer who writes creative nonfiction and fiction. I live in Berkeley.

You’re here because you’ve gone through a fallow period where you didn’t produce much work for a time. How did your Long Pause come about? How long did it last? OR are you still in it?

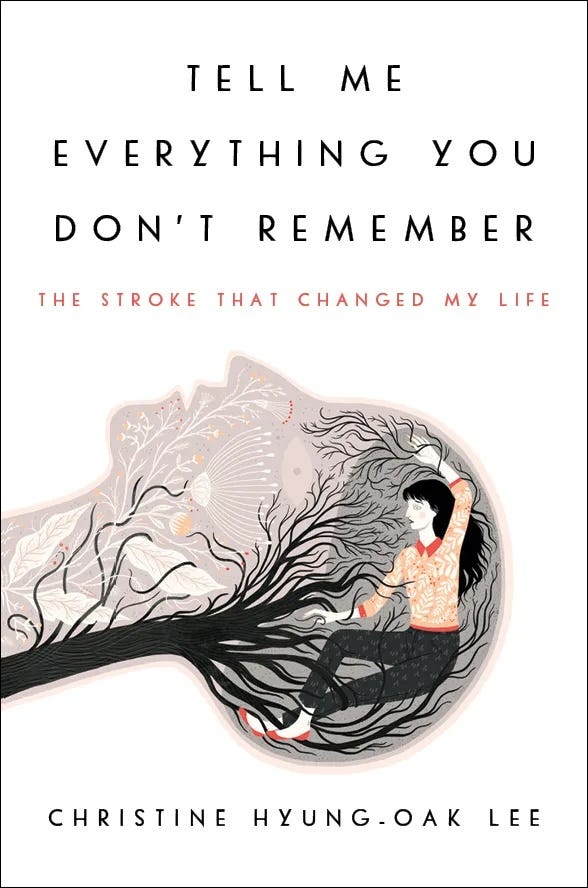

I sold my debut memoir and debut novel in a two-book deal with a Big Five publisher. My memoir, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember, came out in 2017; I got to experience the whirlwind of book launch. I visited the NPR studios in D.C. and met Scott Simon for Weekend Edition. The New York Times reviewed my book. It was a fever dream.

When it all died down, I went back to work on my novel while continuing to write shorter pieces like stories and a column about my urban farm for Catapult magazine (RIP).

Editor’s note: OMG YOU GUYS, Christine keeps bees! *cue fangirl shrieking!*

But then, in 2020, the pandemic arrived. It was stunning to see the world go into crisis mode, the same crisis mode that always seemed to exist in my own traumatized mind. I re-prioritized my life to center my daughter, who was, at the time, in elementary school. It was impossible to write. I was at home all day with my daughter. Everything felt on a precipice.

Also, in 2020, another thing I’ve yet to talk about publicly, happened. After my editor left, my publisher canceled my contract for the novel.

It has taken years to recover from 2020. It’s now 2025. And I’m wending my way back.

Were there positives that came out of your Long Pause? What did you learn or come to terms with while you were blocked?

My first impulse was to say, “Absolutely fucking nothing” positive came out of my Long Pause. But I returned to this question and realized that my Long Pause deeply humbled me. And it forced me to look at myself holistically, becoming a better teacher in the process. I devalued ambition and decoupled my writing from the outcome. I went back to the pure joy of writing. Being demoralized and ripped down to the studs can lay bare the essence of what you desire.

Did you engage with other creative practices while you were blocked from your primary mode of expression during a Long Pause? What did you do? What did you learn?

Thank you for this question. I never did stop being creative. It was just the words and the narrative arcs that stopped; the creative drive was always there in the form of quilting, textile arts…anything low-stakes. Right now, I’m obsessing over building color palettes and learning more about color theory because I’ve transitioned to using solid color fabrics in my quilts (as opposed to patterned fabric). I’m examining fabric layouts and shapes, which reminds me of book structure. I’m certain it’s deepening my relationship with writing, even if in a roundabout way.

The other Long Pause (prior to this one) was when I had a stroke at the age of thirty-three that left me with a fifteen-minute short-term memory and a complete inability to put cohesive narrative together. I kept writing through that, too. Even if it was nonsense sentences in a journal or a blog. It was then that I recognized that I couldn’t not write. And that putting any words down is a way to find my way back. So I never stopped writing in my journal this whole time.

What, if anything, did you learn in a formal learning space (like workshops, an MFA, whatever) about blocks or pauses? Did you have a mentor or teacher who addressed this possibility or modeled how to work with or through a pause?

I had/have a mentor who is transparent about his writer’s block. He’s pretty miserable when he goes through it. Every ten years, he comes out with something utterly genius. He talked about not being a tyrant to your characters and yourself when I was in workshops with him at VONA (Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation). He talked about identifying your Inner Self Critic. He prepared me for the inevitability of such a thing.

HAHA. But we all have our unique journeys. We can have a toolbox with us, but we have to do that walk alone. I’m grateful for the tools he gave me, because they did help. And it certainly helped to know that a lauded writer can struggle.

When capitalist themes bleed into creative work, there is a pervasive pressure to be productive all the time, an assumption that this productivity should translate to profitability, and that because your work is creative (i.e. “fun”) you shouldn’t need to rest. How have these themes impacted your creative work and your Pause?

This. I’m so glad you addressed this. I have a well-worn soapbox about “productivity” and writing.

Our capitalistic society indeed promotes “productivity.” Our visibility is dependent on how much and how often we publish, whether essays, short stories, or books. Our worth is measured by the number of books we sell, the number of viewers, and the number of likes. When you look at a book proposal, writers include how many followers they have on social media and how much traction their prior work has had. That then translates into whether or not you get a book deal, let alone how much money you receive for your book, which becomes your livelihood. That then affects mental health.

That. Is a LOT.

And none of the above respects the writing process. Some of us are just slow-as-molasses writers. Most of us have day jobs and side hustles that make us less productive as writers. Does that make us shitty writers? No.

I’ve recovered from my Long Pause by decoupling the number of finished pieces, income, and metrics from how I judge myself as a writer.

Let me tell you a story. I happen to have an urban farm with chickens, bees, and a foodscape. One year, I signed up to grow and deliver vegetables to a well-known pop-up Korean grocery in San Francisco. I’d grown the vegetables in prior years and had a massive bounty. No problem, right? I’d just do what I usually do!

So I did. I planted the seeds. I watered them. Nurtured them.

I was a nervous wreck throughout. Suddenly, those plants were high-stakes. They weren’t for me. They were for other people. Money was riding on them. I was not having fun growing them. I was miserable.

When they neared maturity, I let the grocery pop-up know.

And they said, “Oh, we’re not ready for them. Maybe in six weeks?”

In my freshman attempt at capitalism on my urban farm, I’d neglected succession planting, when you sow seeds in waves and intervals to ensure a continuous harvest over a longer period. Instead, I’d asked them when they wanted the vegetables and then planted them en masse with that timeline in mind.

As I read their response, every curse word in the book floated through my head.

Guess what: the curse words weren’t directed at them. They were directed at MYSELF. I felt like I’d failed. Suddenly, the thing that brought me the most joy had become a binary of success versus failure. I thought about what I’d do the next year to ensure “success,” and how I’d manipulate farming for a productive outcome. And then I thought about how those were unnatural acts. I thought about how deeply unhappy I would become. I thought about industrial farming, their pressure to increase production, and how those decisions have led to monocropping and ecological ruin. It went on and on.

I had to tell the pop-up the vegetable harvest would be over by then, and none would be available. I decided that profit and loss weren’t compatible with my urban farm. It made me miserable. It made gardening stressful. I wanted to go back to the pure joy of it.

The same goes for my writing.

I also have an anecdote about how my writing, because it’s “fun,” or doesn’t make as much money (a metric) didn’t count as viable work when I used to be married. It’s ridiculous. It’s patriarchy.

Christine Hyung-Oak Lee is a writer and the author of a memoir published by Ecco / HarperCollins, Tell Me Everything You Don’t Remember, which was featured in Self Magazine, Time, The New York Times, and NPR’s Weekend Edition with Scott Simon. Her memoir was also the first illness memoir written by a BIPOC writer published by one of the "Big 5" publishers. Her short stories and essays have appeared in ZYZZYVA, BuzzFeed, Guernica, and The New York Times. She is a VONA Alum. Christine's pronouns are they/she.

IG: @xtinehleewriter

Bluesky: @xtinehlee.bsky.social

Substack: christinehlee.substack.com (Cuddle Fish)

Thank you for this very very important Substack series, @Erinn!

Christine’s writing is fantastic. I loved hearing more about her writing and her other creative work. 💙